[This is a transcript, slightly cleaned up, of a talk I gave earlier today at CSCW 2016. I was asked by Gloria Mark to join a panel on constant connectivity after she read The Distraction Addiction; but rather than give a talk that summarized my earlier book, I decided to use the talk as an opportunity to draw out the connections between that project and my new book, Rest.]

When we were talking about the panel, Gloria asked us each to share a picture that illustrates our thinking about technology. I chose this one:

We all know what the device on the right is; the one on the left is a million year-old hand axe. I put these together to make the point that while we sometimes think that technologies have an alienating or dehumanizing affect on us, the opposite is actually the case. Humans have coevolved with our technologies. We and our ancestors have never lived in a world without technologies, and we wouldn’t be able to exist without them. Not only that, over the years we’ve become really good at using them to extend our physical abilities, augment our cognitive abilities, enrich our extended minds (as Andy Clark puts it)—and to enjoy doing so.

One reason today’s technologies can be so good at capturing attention, and why the stakes in being constantly connected turn out to be high, is that they’re tapping into a profound human ability, and a profoundly humanizing one: this talent for using technologies so well they feel like they’re extensions of us is one of the defining traits of our species. Some of them are designed to perform like weapons of mass distraction, and our tools for capturing and processing attention are getting better all the time; others, like email, are addicting mainly for social and organizational reasons.

So far, critics like Nicholas Carr and Sherry Turkle have mainly been focused on how device and connectivity are cleverly designed to distract us, and more generally erode our ability to focus. That can mean being more prone to distraction when trying to complete a specific task, like having cat videos distracting you from an article you need to read for work.

At another level, it can mean eroding your capacity for focus, which like willpower can be depleted, and get in the way of your ability to finish a big task, like a dissertation.

It’s easy to think that this is a new problem, and that the world used to be a less distracting place. But that would be incorrect. The history of developing tools and practices and spaces to promote our ability to control our mental states—to concentrate on a problem, to clear our minds, even relax our conscious attention—goes back to ancient times. The fact that some of the most popular tools for learning to become aware of the state of our minds, and to move from one state to another, are very old—which tells us that problems with distraction are, too.

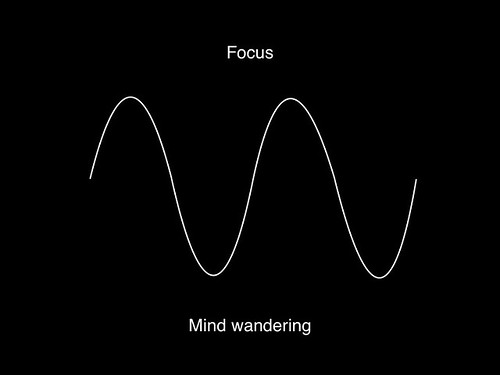

Now, we usually talk about mindfulness and meditation, not control of mental states. Indeed, I wrote a book about how technologies can distract us, and how we can learn to use them to be more focused and mindful. But in the course of writing my new book, Rest, I realized that there was another side to our engagement with devices. They don’t just distract us, or affect our focus. They can also do a good job eroding our capacity for another, less well-appreciated mental state: mind-wandering.

This is not as well-known as focus (and it’s absolutely not the same as distraction), and in our lives we generally don’t feel it’s something worth defending as urgently. But psychologists are finding that mind-wandering isn’t just a kind of energy-saving mode for the brain: during mind-wandering we play our future scenarios, ruminate over past events, and run through possible solutions to problems that we’ve been working on—all without conscious effort, or our being aware that we’re doing it.

There even seems to be a connection between focus and mind-wandering: the more time we spend doing things that allow our minds to relax and unfocus, the deeper our capacity for intense concentration.

Shifting between these two states also helps us to be more creative. We’ve all had the experience of working hard on a problem, then having the answer appear when we’re in line at the store or out on a walk.

In my new book, I argue that creative people design their schedules and habits to support both periods of intense focus, and mind-wandering.

Being aware of our mental states, learning to control them, and understanding our own minds and work well enough to know which state we need to be in, is a great challenge. Most creative figures struggle for years to figure it out.

So how does this relate to technology and connectivity?

Learning to use tools so well that they become extensions of our minds is important for awakening this sense that we can control “the contents of our consciousness,” as William James put it. It’s why children who have time to play seem to have better focus in class. It’s why a surprising number of world-class scientists, engineers, and writers are also rock-climbers, sailors, serious musicians, or artists. It’s why in Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi’s book Flow (if you don’t know it, read these posts) many activities in which people find that optimal state involve using technologies intimately.

So can we design to better support learning how to control our mental states, to drop into intense concentration or mind-wandering? I’m optimistic that we can.

There’s a long history of humans being confronted with new forms of distraction, then developing new techniques to deal with them. In debates about the long-term effect of digital technologies on our minds, attention spans, or sociability, people sometimes point out that Plato complained about writing competing with speech and eroding memory, and that people worried about the impact of the printing press, the telegraph, and newspaper; and the implication is that these complaints fade over time, and people simply adjust. That’s not accurate. People develop techniques to deal with new distractions. We don’t just adapt. We deliberately craft new practices.

Discovering the pleasures of focus, the virtues of solitude, the value of mind-wandering is something most very creative people do as adults, and I think our devices are in a sort of adolescence: we love the easy socialbility, and almost are ready to discover the value of being connected to our work, to engaging problems, and to our minds as well. Designing to support these forms of connection, while recognizing that the process of learning how to use and direct our own mental states is a lifelong challenge, is difficult, but possible (“ease of use” doesn’t mean “an easy life”); and learning to do it will let us help people be not just better connected but better humans as well.