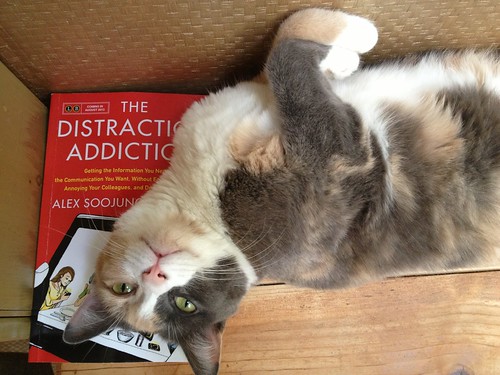

One of the common threads running between Rest and my previous book The Distraction Addiction is that both encourage readers to see themselves as able to resist the temptations and distractions that seem to be an ever-bigger part of our everyday lives. It’s essential to have time to focus to get work done; it’s also essential to have time to mind-wander to get work done; but we lose time to both when we let our attention be captured by shiny-blinky things. (And yes, distraction and mind-wandering are two different things.)

Since The Distraction Addiction came out, lots of people have examined how some companies use behavioral economics and other tools to make games or social software more addictive. Natasha Dow Schüll’s book Addicted by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas is a terrific example of the genre, as is the work of Ian Bogost on video game design that encourages in-app purchases.

Now, it’s long been the case that people have tried to manipulate people through media: a century ago, Walter Lippmann warned us about the ways public opinion was being directed by newspaper publishers and powerful interests, and how mass media were being used to shape public attitudes about big issues. Anyone who’s watched Mad Men knows that the advertising industry has spent decades trying to create demand for goods.

Advertisements in Times Square, New York

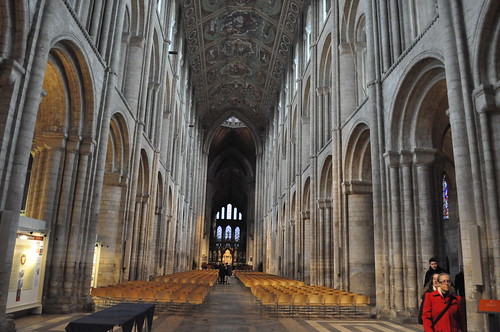

You can even argue that stained glass windows, designed to inspire feelings of piety, and that cathedrals meant to evoke a sense of humility– that these were early classics of behavioral design.

Medieval behavior design: Ely Cathedral

Medieval behavior design: Ely Cathedral

But if anything seems to differentiate Las Vegas from Lourdes, or Zynga from Saint Etheldreda, it’s that today’s games are designed to be addictive, and the best ones are capable of changing based on our reactions. They’re like having a used car salesman in your pocket, always trying to close the deal.

But it’s not always the case that the most distracting technologies are designed that way, or that they’re monetizing distraction.

The great example of a technology that wasn’t created to be addicting, yet has become unavoidable and unstoppable, is electronic mail.

Email is the Ted Cruz of the tech world: it’s universally loathed by smart people, yet somehow seems impossible to get rid of. Indeed, I suspect there are more people in tech who would love to kill email once and for all than would reform it. Any number of companies have gotten funding on the promise to replace email with something faster, or more lightweight, or whatever.

We all know what’s wrong with email: it’s cumbersome, it’s called upon to do jobs it wasn’t meant for, there’s too much of it, and it never stops. But what keeps email around, and keeps it so ubiquitous? No one designed email to be addictive; to the degree that anyone thought much about the design of email at all, it was a copy of interoffice memoranda.

I think sociologist and Guardian contributor Peter Fleming gets at the root causes of our obsession with our in-boxes, a problem that has only gotten worse with the invasion of smartphones, “an almost perfect expression of the ‘never switched off’ employment culture that has been growing over the past 15 years.” The paradox, Fleming notes, is that

there is nothing intrinsic to a smartphone that forces people to send yet another email, sometimes long after the office has closed. It’s just a little piece of plastic and silicon. So the inability to switch off must be symptomatic of other pressures.

No doubt labour intensification is part of the problem – fewer people doing more work, which is a cornerstone employment policy in the age of permanent austerity. However, other changes have also occurred too.

According to an influential group of neoliberal economists working in the 1970s, people ought to see themselves as “human capital” rather than human beings. This sort of capital is a never-ending investment, continuously enhanced in relation to skills, attitude and even physical appearance.

Work is crucial for building this capital, perhaps its defining source. This is where employment and life more generally slowly merge and become indistinguishable from each other. A job is no longer something we do to achieve socially productive goals in society. An activity among other pursuits. No, a job today is something we are … preferably 24/7. Working unpaid overtime therefore seems natural. Self-exploitation looks like personal freedom.

The problem, in other words, is not that we’re victims of clever design that hook into our unthinking monkey brains. Our dysfunctional relationship with email is a function of the working world we inhabit, the culture of the modern workplace, and the belief that work needs to be the “defining source” of meaning and value in our lives. Email isn’t responsible for this; it’s a tool we use to keep ourselves perpetually busy.

Another great example of a tech use phenomenon that doesn’t flow from nefarious design choices is FOMO, which Manoush Zomorodi taks about with Caterina Fake and Anil Dash in her latest Note To Self podcast. Fake first described FOMO in a 2011 article, Caterina Fake talks about how FOMO encourages us to distort our public presentation of self. “constant self-presentation… is a mechanism for resentment, envy, and dissatisfaction.” “this tendency of people to productize themselves,” “to become a shinier, newer, more polished, and ‘better’ version of themselves.”

Technology enables it, but it doesn’t cause it. Caterina Fake didn’t design Flickr to be a platform for broadcasting a carefully-scrubbed, filtered (literally!) public image of your life as a series of fish taco and margarita dinners with BFFs, downtime in the airport first class lounge, and Sundays at the beach.

Flickr “wasn’t a tool for performing yourself to the world” when it first started, Anil Dash says; “it was in most cases about something you created and wanted to share.” But still, many of us use it that way because of social expectations.

The good news is that if email and FOMO are cages, they’re cages of our making; to at least some degree, we consent to live in them. Which means that we can get out of them. Not easily, perhaps— bucking social norms, or your co-workers’ expectations, never is— but these habits are the product of behaviors and assumptions, and aren’t hard-wired into the technology. Which means the cages can be opened and taken down. Because for all our belief in inevitability of technologies, the cages were never there to begin with.

(Fleming, by the way, has built up a rather impressive body of work at The Guardian, and is emerging as one of our sharper critics of the modern dysfunctional workplace.)