Just over forty years ago, Erno Rubik invented what is now one of the most famous puzzles ever: the Rubik’s Cube. Recently I saw an interview with Rubik conducted by one of my former bosses, Paul Hoffman.

Paul Hoffman and Erno Rubik, inventor of the Rubik’s Cube (EG8) from EG Conference on Vimeo.

The interview got me interested in Rubik and how he came to create the Cube. It turns out that Rubik was in his late twenties, teaching at the Academy of Applied Arts in Budapest, and sharing an apartment with his mother. He had studied sculpture in college, and was teaching his students about three-dimensional structures. He had a long interest in geometry and puzzles; the bedroom in his apartment (he still lived with his mother at the time) was stuffed with models and puzzles.

That much is clear, and other parts of the story are told consistently, but there are two slightly different accounts of why he was working on the cube. One is represented by this article in Mental Floss, and the story is recounted as one of a pure intellectual challenge:

In 1974, a particular project had him stumped. For months, he’d been working on a block made of smaller cubes that could move without causing the whole structure to fall apart. So far, each attempt had failed. The evidence was strewn all over the two-bedroom apartment he shared with his mother.

One spring day, a frustrated Rubik left the apartment and wandered the streets of Budapest. He followed a gentle bend in the Danube River, a path he had walked countless times before. At one point, he stopped to listen to the water lapping ashore and looked down at the polished round pebbles that lined the riverbank. Suddenly, his heart started racing.

The solution was right at his feet: If individual blocks hinged on a rounded core, they could move freely while maintaining the shape of a cube. Rubik raced home and created a prototype held together with paper clips and rubber bands—a structure consisting of 21 smaller cubelets, adhered to a rounded interlocking mechanism.

In other tellings, the project is sparked by his teaching. For example, Rubik told The Guardian in 2012,

I was searching for a way to demonstrate 3D movement to my students and one day found myself staring into the River Danube, looking at how the water moved around the pebbles. This became the inspiration for the cube’s twisting mechanism. The fact that it can do this without falling apart is part of its magic.

I experimented in my mother’s flat, using wood, rubber bands and paper clips to make a prototype. I needed some sort of coding to bring sense to the rotations of the cube, so I used the simplest and strongest solution: primary colours. Putting the stickers on the finished cube felt very emotional.

As he told CNN in 2012, “Usually structures are pieces that are connected in some way or another,”

and usually these connections are stable things. So all the time “A” is connected to “B.” But with the structure of the Rubik’s Cube, you realize these elements are moving very freely, but you don’t understand what keeps the whole thing together, so that was a very interesting part of it.

A 1986 Discover Magazine article explicitly favors the first account over the second:

Many of the early stories about the Cube related that it was built to teach Rubik’s students how to “deal with three-dimensional objects.” I never understood what this meant, much less how the Cube could teach it. The mystery was cleared up after I arrived in Budapest. At the Academy they chuckled at the thought of using the Cube in class, and Rubik dismissed the idea. Yes, he had shown the Cube to his students, but he hadn’t built it for them. He built it because he was a designer who likes playing with geometric shapes.

But no matter how it starts, Rubik’s story is almost a perfect example of the four-stage model of thinking and discovery that Graham Wallas outlined in his classic 1926 book The Art of Thought. (Wallas never uses the word “creativity,” by the way.)

When working on difficult problems, Wallas argued, people generally go through four stages.

The first stage is Preparation: they organize a line of attack, consciously work through alternatives, and eliminate possibilities. Sometimes this is enough to solve a problem, if it’s not too hard; but most interesting problems don’t give up so easily.

With the harder ones, there follows a second phase: Incubation, a period of “voluntary abstention from conscious thought on any particular problem.”

Mental relaxation during the incubation stage may of course include, and sometimes requires, a certain amount of physical exercise…. When I once discussed this fact with an athletic Cambridge friend, he expressed his gratitude for any evidence which would provide that it was the duty of all intellectual workers to spend their vacations in alpine climbing.

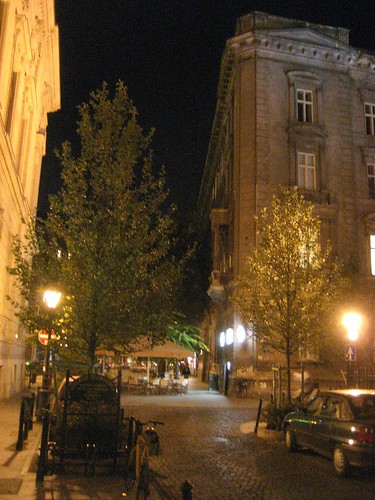

There are also countless stories of people going on walks in this phase. I don’t know where Rubik was living, but the walk along the Danube detail makes perfect sense to me, since the river runs right through Budapest.

In fact, for a long time the city was two cities on opposite sides of the river, Buda and Pest. Only in the late 1800s, with the building of permanent bridges across the Danube, were they formally united.

After some period, this period ends with a sudden third phrase, Illumination, in which the answer suddenly dawns (or is suddenly present in the conscious mind). This is the moment of insight, the a-ha moment, the epiphany, whatever you choose to call it.

The fourth and final stage, when the new idea is tested, and a proof worked up or prototype finished, is Verification.

Whatever the inspiration, there are elements of the Rubik’s Cube story that are pretty consistent: his working on the problem for a long time (Preparation); being stumped with the problem of how to hold a three-dimensional structure of multiple cubes together (Incubation); taking a walk along the Danube, and seeing in the movement of the water around the pebbles the solution to the twisting mechanism problem (Illumination); and a few days’ work to build the first prototype (Verification).

But the discovery of the Rubik’s cube structure is only the first moment of inspiration in the story. There’s a second. As he wrote in an unpublished autobiography, Rubik put colored stickers on the cubes as a way of keeping track of them. But at one point he noticed something cool:

It was wonderful to see how, after only a few turns, the colors became mixed, apparently in random fashion. It was tremendously satisfying to watch this color parade. Like after a nice walk when you have seen many lovely sights you decide to go home, after a while I decided it was time to go home, let us put the cubes back in order. And it was at that moment that I came face to face with the Big Challenge: What is the way home?

Two things are striking about this. First, there’s the metaphor of the walk again. You’ve been out made some nice discoveries, seen “lovely sights,” and now it’s time to go home. Solving the puzzle is a kind of homecoming.

The second is that this makes clear that Rubik didn’t set out to design a puzzle. He set out to create a cool three-dimensional structure. It was only after he had built it that he discovered it was also a puzzle.

It took him a month to solve puzzle. At first, he wasn’t even sure it was possible: after all, the cube has some 43 quintillion possible combinations. As he told Discover, working on it was like “staring at a piece of writing written in a secret code. But for me, it was a code I myself had invented! Yet I could not read it. This was such an extraordinary situation that I simply could not accept it.”

The first time he solved it, he said in his CNN interview, “it was a very emotional feeling.” His mother was happy, too, he told Discover: “I remember how proudly I demonstrated to her when I found the solution of the problem, and how happy she was in the hope that from then on I would not work so hard on it.”

But the cool thing about the cube is that, because it’s so much of a challenge, it’s not like a game where once you know the solution, you’re done. As he explained in the CNN interview:

But then it’s not something like a jigsaw puzzle where you start to work on it, spend some time on it, and in the end it’s solved, it’s finished. If you find a solution with the cube, it doesn’t mean you find everything. It’s only a starting point. You can work on and find something else, you can improve your solution, you can make it shorter, you can go deeper and deeper and collect knowledge and many other things.

Or, as he put it in the Discover article, “with the Cube there are many flashes [of insight], there are many a-ha’s.” The Cube is a generator of a-ha moments that is itself the product of an a-ha moment.