To hear Nicholas Carr and Sven Birkets tell it, the Web makes you stupid in two ways. There’s the performative sense: being on the Internet shrinks parts of your brain that deal with really complex reasoning. And there’s the cultural sense: you have less exposure to, or interaction with, Serious Thoughts. In both cases, though, you’re distracted by the infinite Internet Fun House from your original task: you sit down to read War and Peace or looking up the atomic weight of strontium, but end up watching a YouTube video of a monkey and a parrot playing ping pong.*

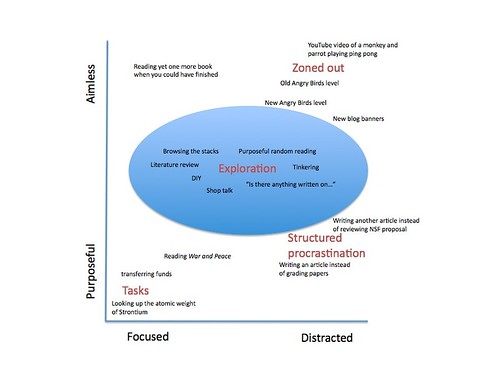

In this formulation, being focused and purposeful is good, while anything that leads you to watch teenage Japanese boys take whiffle ball hits to the crotch on a game show is bad. In the graphic below, imagine going from the bottom left corner to the top right.

But there’s also an assumption that those are the only two modes– focused and on-task, versus scattered and fractured. I think, however, that we need to recognize that there’s a zone in the middle that consists of a variety of intellectual tasks, which are more or less directed or structured, and more or less “productive”, but very much worth recognizing as part of our intellectual lives.

So what else is there between looking up atomic weights and YouTube videos of game-playing animals? You might think of structured procrastination as occupying part of another quadrant. Writing an article instead of grading papers, or writing another article instead of reviewing a grant proposal, are activities that are purposeful yet distracted: you know you should be doing something else, but you’re putting it off by doing this other thing.

Other sorts of procrastination might be focused but aimless: reading a few more books so you can add more footnotes to the dissertation you’ve already finished would be an example.

And of course there are different levels of zoning out, some of which might be a little more engaging than others (e.g., playing a new Angry Birds level rather than replaying an old Angry Birds level).

Roughly in the middle, though, there’s an area of activities that you could call exploratory. These don’t begin with some specific question that needs an answer (e.g., what’s the atomic weight of strontium). Here, you might ask a particular question, but your aim isn’t to generate or acquire a piece of information, but to use the question as a probe into a bigger territory. You might browse the stacks, or the contents of a journal. You might spend some time looking at something you normally don’t look at, because you want to be exposed to something different but potentially useful. Or you might think about how two different things you’ve been reading might fit together. (I’ve been reading Michael Lewis’ The Big Short, for example, and am starting to think that the concept “attention economy” does for people’s minds what the CDO did for people’s homes. Not an obvious connection, but one I’m trying to flesh out.)

The point is, when you’re in the middle of these activities, it’s not really clear which ones are going to pay off, and which aren’t; it’s not just hard to figure out, it’s completely impossible to do so. At some points in the creative process, it’s useful to spend some time on the boundaries of order and randomness, or distraction and focus: it’s a less “efficient” way of finding specific facts, but a potentially fruitful way to generate new ideas.

*Incredibly, there does not seem to be a video of a monkey AND a parrot playing ping pong. There’s a parrot playing ping pong, however.