Sherry Turkle recently published an op ed in the New York Times about selfies and "The Documented Life." In it, she argues that the focus on taking selfies, on self-documentation, and our willingness to interrupt our lives in order to document our lives gets in the way of living:

A selfie, like any photograph, interrupts experience to mark the moment. In this, it shares something with all the other ways we break up our day, when we text during class, in meetings, at the theater, at dinners with friends. And yes, at funerals, but also more regularly at church and synagogue services. We text when we are in bed with our partners and spouses. We watch our political representatives text during sessions.

Technology doesn’t just do things for us. It does things to us, changing not just what we do but who we are. The selfie makes us accustomed to putting ourselves and those around us “on pause” in order to document our lives. It is an extension of how we have learned to put our conversations “on pause” when we send or receive a text, an image, an email, a call.

Why is this a problem? Because, Turkle argues, "When you get accustomed to a life of stops and starts, you get less accustomed to reflecting on where you are and what you are thinking." It makes it less likely for us to "have serious conversations with ourselves and with other people," or simply "sit still with our thoughts."

But all is not lost:

It is not too late to reclaim our composure. I see the most hope in young people who have grown up with this technology and begin to see its cost. They respond when adults provide them with sacred spaces (the kitchen, the family room, the car) as device-free zones to reclaim conversation and self-reflection.

Now, to readers of Alone Together, this will sound familiar. Turlke argues in that book that too often, interaction with technology serves as an easy, self-distracting substitute for the harder but ultimately more fulfilling work of interacting with people. The painful irony is that while these technologies offer the opportunity to make us more "social," they leave us less capable of being social.*

Jason Feifer at Fast Company dismissed her as "scaremongering" in an essay titled "Google Makes You Smarter, Facebook Makes You Happier, Selfies Make You A Better Person." His response to Turkle:

Have you ever pulled your friends together for a photograph, and struck a pose? Have you ever crowded heads with your boyfriend or girlfriend, making faces into a camera to make each other laugh? These aren’t interruptions of a moment; they are a moment. Some selfies are frivolous, of course, but so are some conversations. Technology can create togetherness….

Turkle imagines that any interaction with technology somehow negates all the time spent doing other things. She also imagines that we must devote ourselves in only one way to every task: At a dinner table, we are only serious and focused on conversation; at a memorial service, we are only mournful.

The message is reinforced by the article's banner picture, a kind of visual illustration of an Upworthy level of amazement:

This woman used the Internet. You won't believe what happened next.

There are two points I want to make. First, critics are missing an important part of Turkle's argument. And second, everyone in this argument has an unhelpful model of how technologies affect us.

Selfies vs. Self-Understanding

First of all, Turkle isn't arguing that this selfies– or other technology-mediated engagements with others and the world– are always bad. Believe me, she's too smart for that. What this essay argues is that this kind of easy self-occupation and self-distraction reduces the space in which we can make sense of ourselves. Note that she talks about having "serious conversations with ourselves" as well as others. And why is sitting "still with our thoughts" important? Because it "does honor to what we are thinking about," and "does honor to ourselves."

That is the central point of this article. For an academic like Turkle, the notion that the unexamined life is not worth living (as the Greeks would have put it) is self-evident. This is one of the oldest and most important functions of philosophy and higher education, and cutting it off– substituting selfies for self-understanding, as it were– is one of the most destructive effects of distracting technology and social media.

The idea that you need periods of silence, or quiet, or leisure, or slowness, to make sense of your life is not exactly new. It's a line of argument that you can find in Thomas Merton and every other contemplative who's ever said more than two words. Unfortunately, it's a point that Feifer and other critics miss in their eagerness to defend Facebook.

So they overlook the main point of Turkle's argument in favor of the shiny-blinky distraction of "Internet BAD!" This is Doge-level analysis.

The Vitamin Theory of Interaction

But if they elide her main argument, they end up replicating one of her flaws. Feifer is right that Turkle proposes a binary choice: you can either use devices that bleed you of your capacity for deep feeling and useful boredom, or you can drop them and reclaim your humanity.

The problem with both Turkle's essay and Feifer's response is that they both treat our relations with technology as kind of like Newtonian physics, as describeable by laws of cause and effect: using this technology does that to us. It reflects what I'm starting to think of as the Vitamin Theory of Interaction With Technology, that our interactions with technology are as predictable and easy to understand as the effects of vitamins on our body. Vitamin A does this, Facebook does that; C does this, Twitter does that.

Turkle in her New York TImes piece focuses on the downsides, and how self-distraction is ultimately self-destruction, while Feifer emphasizes the upsides of connecting with others through technology. But both frame the arguments in a language of cause and effect.

The problem is that this model is utterly wrong. Context and intention, for example, really matter in shaping how use use technologies, and what we get out of them. As I talk about in my book, people who like Zenware like it not just because of the formal benefits or the cool design. They like it because it reminds them of the need to focus, and serves as an external expression of a commitment to be concentrate. For Buddhist monks who live in monasteries, the fact that the sacred and profane are one screen away from each other presents a challenge to be extra mindful when online.

To take an example from the end of Feiler's essay:

Is it good that a dad pays more attention to Google than his daughter? No, of course not. That guy should put down his phone. But we should be careful about distinguishing between actual problems and perceived ones. The phone is not, by itself, the problem. In fact, if that dad closed his Google app, opened his camera app, and took a selfie with his 14-year-old daughter, I bet she’d be thrilled.

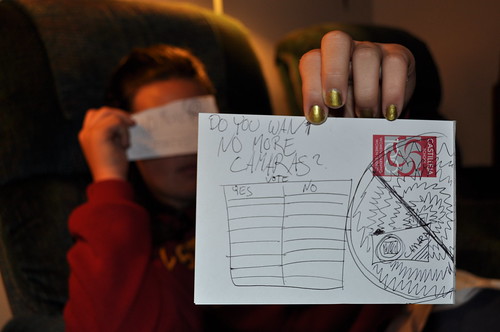

Or she might react the way my daughter reacts.

In other words, while it would be convenient if our interactions with technology were like physical phenomena, they have a phenomenology that we cannot ignore.

Photography can take us out of world, or encourage us to pay closer attention to it. But the camera doesn't change the way we see the world; learning to use the camera, the practice of seeing the world through it, is what changes us. Practice, not the product, is what affects us. It's not phenomenon, it's phenomenology.

*Another issue I had with Alone Together was that the book's core studies involved groups who are socially marginal in ways it never acknowledges: its description of a project to give robotic seal-like creatures to elderly people in nursing homes doesn't talk about how this population can often be socially isolated, dealing with higher-than-average rates of depression, and thus more likely to want to interact with both a robot seal and graduate students running the experiment. Trying to extract Big Lessons About The Modern Condition from studies of little kids and isolated elders seems a little problematic to me.