This afternoon I went to the Jewish Museum Vienna. The museum is located near Stephensplatz, in the center of the city, in a building that was once the residence of a Hungarian count, and later an art gallery. I had heard good things about it, but I was completely unprepared for how unexpectedly brilliant and moving it is. Of course, anyone who knows anything about the history of Europe should have some passing familiarity with the brilliant and tragic history of the Jewish community in Vienna. But the experience of the museum isn’t powerful because it plays on your emotions in obvious ways: it’s not a kind of material version of Schindler’s List. It’s an amazing experience for other reasons.

The bottom floor is dominated by a large room with selections from the Max Berger Collection of Judaica. The room itself has a curved wall that stretches to the top floor.

via flickr

It reminded me of Adolf Loos’ Steiner House, one of the great milestones of early Viennese modernism.

steiner house, vienna

The exhibit is in one long case, with selections from the Torah etched on the glass in front of the objects.

via flickr

The placement of the words is unconventional to say the least, and the intention is twofold. First, it’s meant to remind you that the objects were used in rituals that were communal and spoken, and were themselves representations of the divine: in a way, the words are what you should focus on, and the objects are their mere physical expression. Second, the words present a challenge: you have to choose to look past them to see the objects. Seeing objects and their history actually isn’t easy, and the design of the exhibit highlights this fact.

Now if this all sounds kind of postmodern, you’re exactly right. Indeed, the whole museum is saturated with an awareness of the complex nature of representation: the current exhibit on stereotypes, for example, talks about this a lot (no surprise).

via flickr

It’s hard to talk about stereotypes and not sound kind of saccharine or predictable: even if you try to apply some reflexivity or rigor, people who study stereotypes tend to conclude that “stereotypes are bad.” I haven’t seen someone (say) deconstruct Amos and Andy and conclude that black people really are awfully funny when they shuffle.

via flickr

But even the stereotypes exhibit– inevitably titled “typical!”– is saved by the amazingly good design. Everything about the exhibits is carefully constructed: the lighting is terrific, the artifacts are well-placed, the rooms flow into each other smoothly, and there are all kinds of interesting choices– the scrims that hold the captions and gently divide rooms, most notably– that make the experience a lot more compelling that I expected. Too often we associate this kind of perfectionism with a lack of passion and creativity: real creativity is messy and ragged and inspired, grunge rock rather than Chopin. But that’s not at all true: perfectionism can communicate a level of reverence for craft and content that forces you to take its subject more seriously.

via flickr

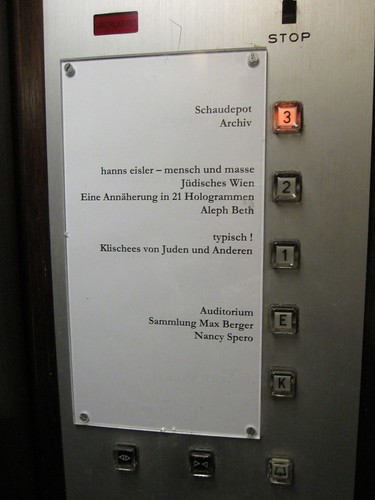

That experience of consciously looking through— looking through words etched in glass, through cloth, through one’s own perceptions and limitations– in the Berger Collection and typical! reaches a climax in the viewable storage room in the archive, on the top floor.

via flickr

Actually, that’s not quite true. It’s more complicated than that. In a normal museum, there are objects that are stored away and inaccessible to the public. The visible storage room, as the name suggests, makes the storage of objects… visible. There are map drawers, climate-controlled storage for textiles, and movable stacks, all the kinds of things that historians are familiar with. Even if you’re not someone who’s spent time in archives, you might find that infrastructure kind of interesting; but if like me, and you’ve literally grown up in archives (when I was a kid I went with my father to the National Archives in Rio, and sat in the reading room and read science fiction while he read notarial documents… or whatever), the experience is really striking.

via flickr

But the more I took in the storage area, the more remarkable it seemed. Some of the artifacts had been damaged in the attacks on Jews in 1938, and they’d never been repaired: you could still see the burn marks on some of the Torah covers. And the reason this collection exists is that the civilization that produced it was very nearly completely destroyed: Vienna in particular had one of the most prosperous and accomplished Jewish communities anywhere, and that world was eradicated almost overnight. The collection is a witness to that tragedy… and it exists in part because of it.

While it’s described as a visible storage area, you can only see things on the outer shelves; the next shelves are faintly visible… but after that, objects recede into obscurity. Visibility shades into invisibility. You’re aware of the objects, but just as aware of everything you can’t see: tens of thousands of artifacts, boxes and boxes of material.

via flickr

So the collection is visible and accessible, but at the same time what you can see reminds you of everything that’s invisible and inaccessible; it’s dedicated to preservation, but some of what’s being preserved is a record of destruction. Like the practice of history itself, it demonstrates how we can examine and ponder the records of the past, but never really get to the people and age that made them. It’s like a beloved person who’s physically close, but firmly and permanently out of reach. All these ideas are stock in trade among historians trained in postmodernism, and I’ve known them for years; but I’ve never seen postmodernism put to so serious a purpose, nor its ideas used with such gravity and grace.

There are times when you’re confronted with something so brilliant and devastating it’s almost overwhelming. Maybe it was the combination of jet lag and overwork, but the brilliance of the idea of the visible archive, the amazing care that went into it, the seriousness with which it uses concepts about history and memory that too often are used for merely clever and sophistic purposes, and the history of the artifacts themselves, made this one of those times for me. For minutes I stood there, not daring to move, not wanting it to end, amazed at how perfect and piercing it all was.