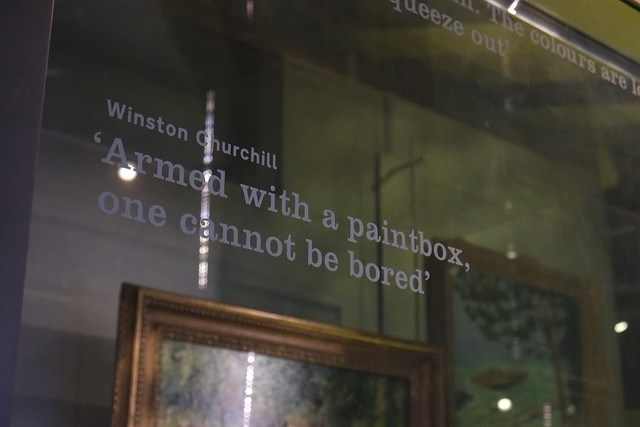

One of the best things my wife and I did in London last year was visit the Churchill War Rooms. I had just come from LSE, where I was reading the Graham Wallas papers, and so I was thinking a lot about rest in creative lives when we toured the War Rooms; and as a result, I was really struck by the display explaining how important painting was to Winston Churchill.

As he explains in Painting as a Pastime, having some kind of hobby is valuable because the mind doesn’t just rest on command; indeed, for busy people it’s hard for the mind to rest at all.

It is no use saying to the tired ‘mental muscles’… ‘I will lie down and think of nothing.’ The mind keeps busy just the same. If it has been weighing and measuring, it goes on weighing and measuring. If it has been worrying, it goes on worrying. It is only when new cells are called into activity, when new starts become the lord of the ascendant, that relief, repose, refreshment are afforded.

If this something else is rightly chosen, if it is really attended by the illumination of another field of interest, gradually, and often quite softly, the old undue grip relaxes and the process of recuperation and repair begins.

The cultivation of a hobby and new forms of interest is therefore a policy of first importance to a public man. (Winston Churchill, Painting as a Pastime) Or as Wilder Penfield put it in The Second Career, “Real rest from the day’s job is doing something else, doing something that brings you delightful preoccupation such as come to a child in his play.”

This idea of rest or leisure as an active thing, rather than passive, is one that you see repeated by lots of really accomplished and creative people. Seeing it over and over is one of the things that convinced me when I was writing Rest that there was actually something new to say about the subject– or rather, that there was something essential about the way creative people think about rest that we’ve forgotten and would do well to remember.